"Our d0 agent has completely changed the way I work. I can't imagine doing my job without this capability."

That's Guillermo Rauch, CEO of Vercel, talking about an internal AI agent that lets anyone at the company ask data questions in Slack. But the fascinating part isn't what d0 does. It's how they made it work.

They deleted 80% of their tools. And performance went through the roof.

If v0 is Vercel's AI for building UI, d0 is their AI for understanding data.

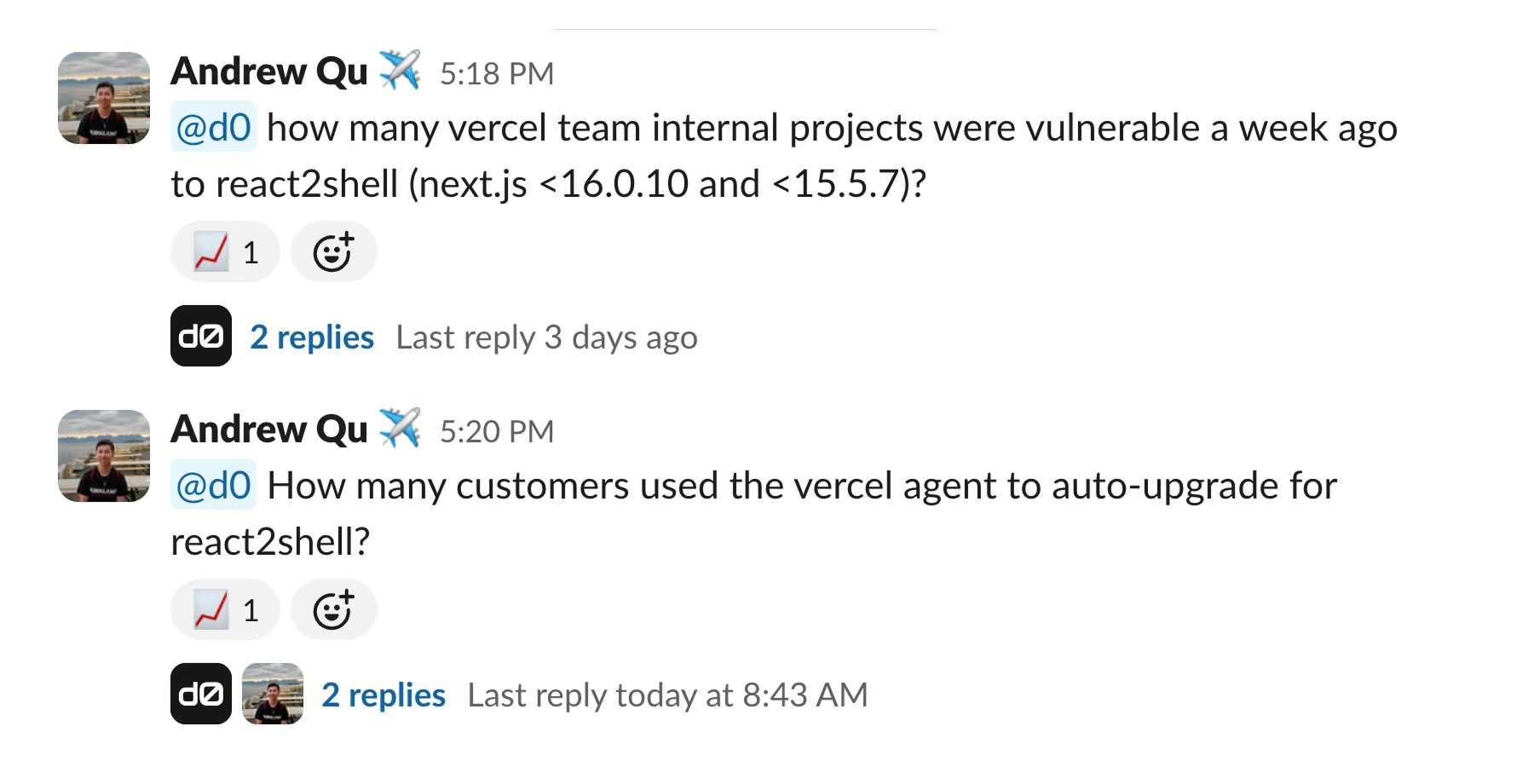

d0 lives in Slack. Anyone at Vercel can ask it questions like:

"Hey @d0 tell me the Vercel regions with most Function invocations?"

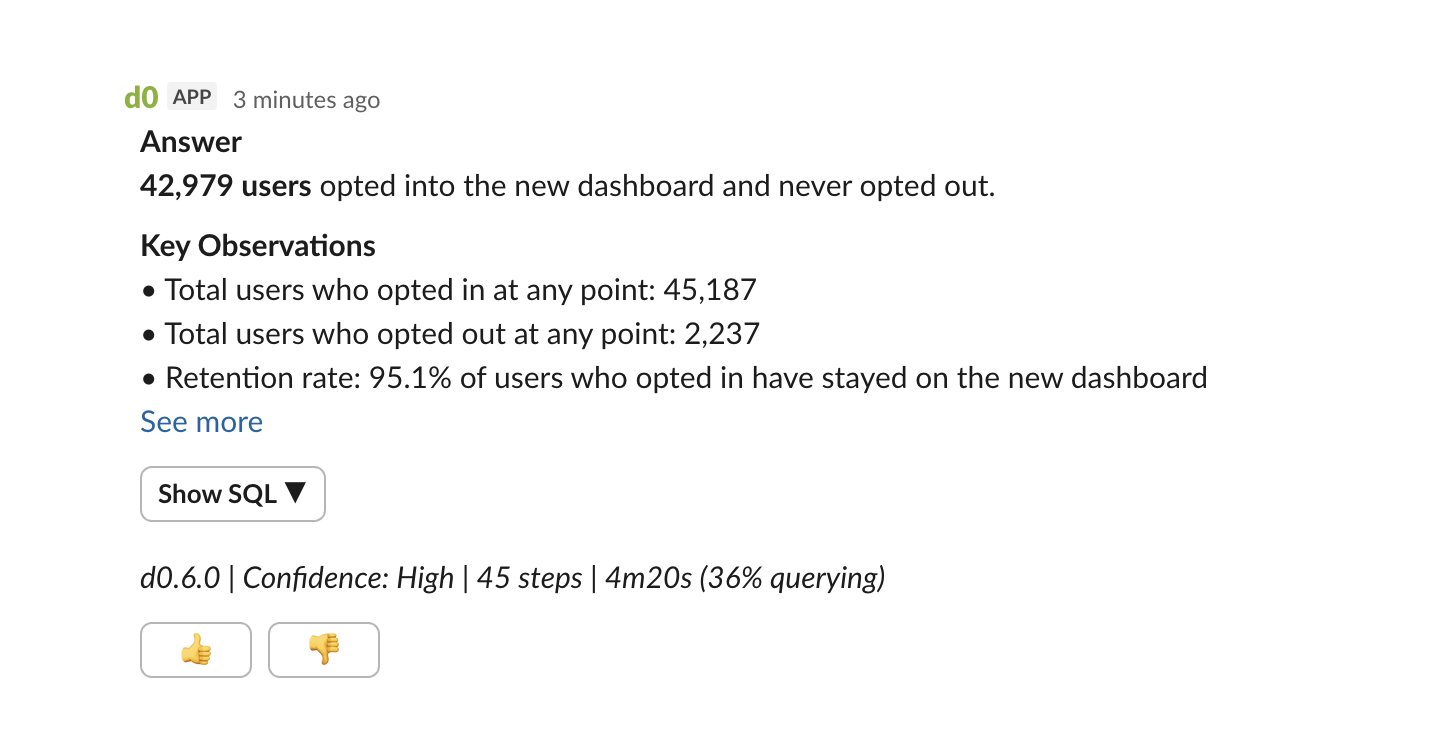

"@d0, how many users opted into the new dashboard experience and stayed opted-in?"

"@d0 how many vercel team internal projects were vulnerable a week ago to react2shell?"

And it returns answers, with the SQL to back them up:

No waiting for the data team. No learning a BI tool. Just ask.

Rauchg's enthusiasm is telling: "We tried for years to get the 'Jarvis of data' working. Opus 4.5 + Sandbox + Gateway has made it possible. There's no going back."

This is the promise we've all heard about AI and data: natural language to insights. But the implementation details are what make d0 interesting.

Vercel's team spent months building d0 the way most of us would. They created specialized tools for every task the agent might need:

Eleven tools in total. Each one carefully designed. Heavy prompt engineering. Careful context management.

It worked... kind of.

80% success rate. Which sounds okay until you realize that means one in five questions failed. For a tool meant to replace asking the data team, that's not good enough.

The agent was slow. It used lots of tokens. It required constant maintenance. When something broke, debugging meant tracing through a maze of specialized tools and handoffs.

The breakthrough came from an unlikely source. Drew Bredvick (@DBredvick), an engineer at Vercel, had been building their AI SDR agent using a radically simple approach: just give the agent a filesystem and bash.

Andrew Qu saw Drew's results and decided to try the same pattern with d0. As he posted on X:

"After hearing about @DBredvick's success with building an agent that just has a filesystem, I rewrote d0, our internal data analyst agent, with a similar pattern. The improvements from the rewrite are night and day!"

The new architecture has essentially two capabilities:

That's it.

The agent now explores Vercel's semantic layer the way a human analyst would. It runs ls to see what files exist. It uses grep to find relevant definitions. It cats files to read dimension and metric definitions. Then it writes SQL based on what it discovered.

The results:

Metric | Before | After ----------------|----------|---------------- Success rate | 80% | 100% Speed | Baseline | 3.5x faster Token usage | Baseline | 37% fewer Steps per query | Baseline | 40% fewer

Not marginal improvements. A fundamental leap.

This seems backwards. More capability should mean better results, right?

Vercel's team explained it clearly:

"We were doing the model's thinking for it."

When you build a specialized tool for "get table information," you're telling the agent: "When you need schema info, use this black box." The agent becomes a router, deciding which tool to call next.

But modern LLMs (Claude, in Vercel's case) are remarkably good at reasoning. They've been trained on millions of examples of developers navigating codebases, grepping through files, piecing together understanding from scattered documentation.

By giving the agent filesystem access instead of specialized tools, Vercel let the model use skills it already had. The agent isn't routing between tools anymore. It's thinking about how to answer the question.

There's a critical piece that makes this work: Vercel's semantic layer.

Their data definitions aren't locked in a database or BI tool. They're YAML files in a repository that the agent can browse like any codebase.

src/semantic/

├── catalog.yml # Index of all entities

└── entities/

├── Company.yml # Company entity definition

├── People.yml # People/employees entity

└── Accounts.yml # Customer accounts entity

The catalog.yml file is the entry point, a registry of all available entities:

entities:

- name: Company

grain: one row per company record

description: >-

Company information including industry classification,

size metrics, and location data for analyzing business

demographics and organizational characteristics.

fields: ['id', 'name', 'industry', 'employee_count',

'revenue', 'founded_year', 'country', 'city']

example_questions:

- How many companies are in each industry?

- What is the average revenue by industry?

- Which companies have the most employees?

use_cases: >-

Market segmentation and industry analysis

Company size and revenue distribution reporting

- name: Accounts

grain: one row per customer account record

description: >-

Customer account records with contract details, revenue

metrics, and relationship information.

fields: ['id', 'account_number', 'company_id', 'status',

'account_type', 'monthly_value', 'total_revenue']

example_questions:

- What is the total monthly recurring revenue?

- How many accounts are Active vs Inactive?

- Which account managers manage the most accounts?

Notice the example_questions. This is genius: the agent can grep for keywords from the user's question to find relevant entities. Netflix's LORE uses similar semantic layer principles for explainability.

Each entity file contains everything the agent needs to write SQL:

# entities/Company.yml

name: Company

type: fact_table

table: main.companies

grain: one row per company

description: Company information including industry, size, and location

dimensions:

- name: industry

sql: industry

type: string

description: Industry sector

sample_values: [Technology, Finance, Healthcare, Retail]

- name: employee_count

sql: employee_count

type: number

description: Number of employees

- name: revenue

sql: revenue

type: number

description: Annual revenue in USD

measures:

- name: total_revenue

sql: revenue

type: sum

description: Total revenue across companies

- name: avg_employees

sql: employee_count

type: avg

description: Average number of employees per company

joins:

- target_entity: People

relationship: one_to_many

join_columns:

from: id

to: company_id

- target_entity: Accounts

relationship: one_to_many

join_columns:

from: id

to: company_id

This is similar to LookML or dbt's semantic layer, but stored as plain files the agent can read.

When someone asks "What's the average revenue by industry?", the agent:

The key insight from Vercel's blog: "LLMs have been trained on massive amounts of code. They've spent countless hours navigating directories, grepping through files... If agents excel at filesystem operations for code, they'll excel at filesystem operations for anything."

The YAML format is both human-readable and machine-readable:

As Rauchg noted: "The agent is extremely effective thanks to our semantic layer defining the 'vocabulary' of how we reason about our business."

This is the insight that's easy to miss. The simplified tooling works because the semantic layer provides structure. Without clear definitions of what data exists and what it means, the agent would be lost.

If you're a Head of Data or Analytics Engineer, here's why you should care: OpenAI's six-layer context system shows how larger organizations solve the same problem with more infrastructure.

The common thread in every successful AI data agent is a well-documented semantic layer. Whether it's dbt semantic layer, Looker's LookML, or YAML files like Vercel's, the AI needs a source of truth for what data means.

If your data definitions live only in tribal knowledge or scattered documentation, AI agents will struggle. The investment in semantic infrastructure pays dividends when you want to layer AI on top.

Already have a semantic layer? You're ahead. If you're using:

The question becomes: can your AI agent access these definitions at runtime?

The instinct is to build specialized tools for every use case. Resist it. Every specialized tool you build is:

Start with primitives. Add specialized tools only when you've proven they're necessary.

Vercel's conclusion is striking:

"Maybe the best architecture is almost no architecture at all. Just filesystems and bash."

This applies beyond text-to-SQL. Whenever you're building AI for data, ask: "Am I adding complexity that prevents the model from doing what it's already good at?"

Notice how Vercel's catalog includes example_questions for each entity. This isn't just documentation; it's a retrieval mechanism. The agent can grep for keywords from the user's question to find the right entity.

If you're building a semantic layer for AI, include example questions. They bridge the gap between how users ask and how data is structured.

d0 represents a shift in how we think about AI agents. The first generation of agent architectures focused on giving AI capabilities: more tools, more functions, more specialized logic.

The emerging approach focuses on giving AI access: access to information, access to execution environments, access to the same resources a human would use. Then trusting the model to figure out how to use them.

This doesn't mean tools are useless. You still need a way to actually run SQL. You still need sandbox environments for security. But the balance is shifting toward fewer, more general tools with richer context.

For data teams, this means:

We've been building AI agents for data analysis for several years now. We connect to warehouses, generate SQL, create visualizations, answer business questions.

Our experience aligns with what Vercel discovered: the power isn't in the number of tools you give an agent. It's in the quality of the context and the room you give it to reason.

When we've simplified our agent architecture (consolidated tools, invested in better prompting, trusted the model more) we've seen the same pattern. Better results. Faster responses. Fewer failures.

The details of our approach are different from d0's. We work across different data sources, handle visualization, operate in different channels. But the principle is the same: give capable models room to think.

If you're exploring AI for your data team, we'd love to show you what we've built.